My friend Dales’ little Sheltie, Kenzie, is here for a visit, once again a warm, furry body helps with artistic juices in the studio.

© 2016, Louise Levergneux, Kenzie

I present two other artists with artwork that continues the theme of muses—our canine companions.

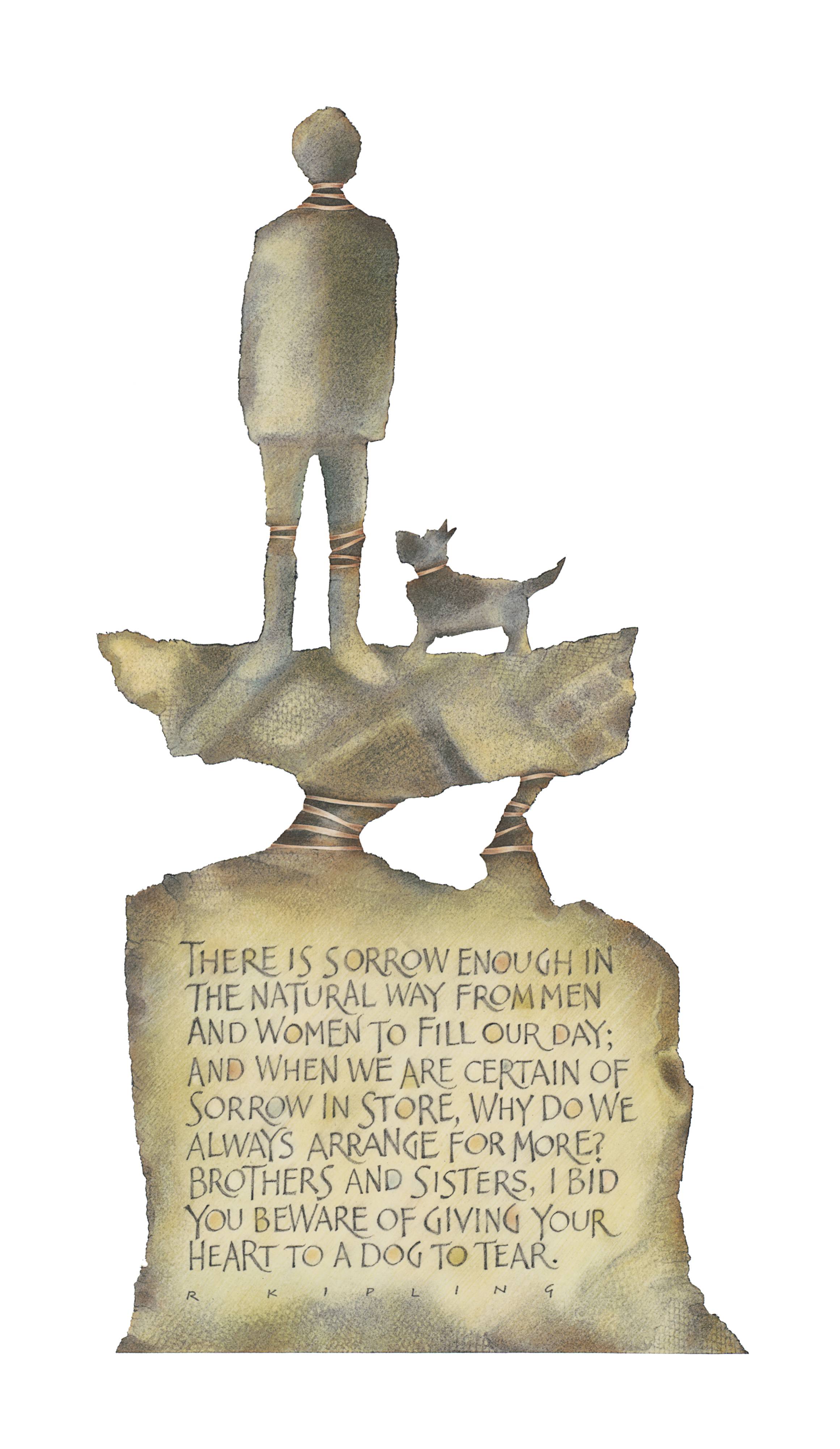

Rebecca Wild is a Pacific North-West artist and calligrapher from the Olympic Peninsula of Washington. Her work pairs a love of letterforms with the luminous characteristics of drawing materials and paint. She uses text as a tool for both conveying a message and creating abstraction.

© 2012, Rebecca Wild, Giving Your Heart is an archival pigment print with charcoal, pastels, graphite, and acrylics that expresses the loss of a beloved companion

Rebecca explains her piece Giving Your Heart:

Several years before the commission of this piece, (by the owner of a Scottish terrier), I discovered the poem, The Power of the Dog by Rudyard Kipling. I had recently lost an elderly canine companion and found comfort and humor in Kipling's words. Although it is one stanza of the poem, it still addresses that inexplicable bond between man and dog. Through simple gesture and form, I hope to pay homage to this unique connection. As he stands at the foot of his master, gaze upward, the dog's devotion is clear.

In the next piece, Rebecca portrays her own loss in Time Undone.

© Rebecca Wild, Time Undone is an archival pigment print with charcoal, pastels, graphite, and acrylics, (4.5w x 11h inches)

How does one put into words the loss of a beloved pet?

I was raw with grief from the unexpected and untimely death of my dog. Although we were not Ruthie’s first home, her 8th to be exact. Ruthie, worked her way into our hearts and home. With a bond so strong, her passing still stings all these years later. She was an unforgettable character of the first degree.

Several weeks after she died, my calligraphy student, Eliza Lindsay, wrote this poem after parting with her dog companion of 16 years, Rosa. She lettered the poem for a class assignment. When I read it I knew I had found words that allowed me to put closure on my loss. The image at the top is my husband beside Ruthie, her head cocked, looking for the next adventure.

Deborah Williams is a nationally recognised visual artist living in Melbourne, Australia. Deborah struggles to have her subject “the dog” worthy of consideration as true culture or high art. Deborah also has a completly different aproach to her subject.

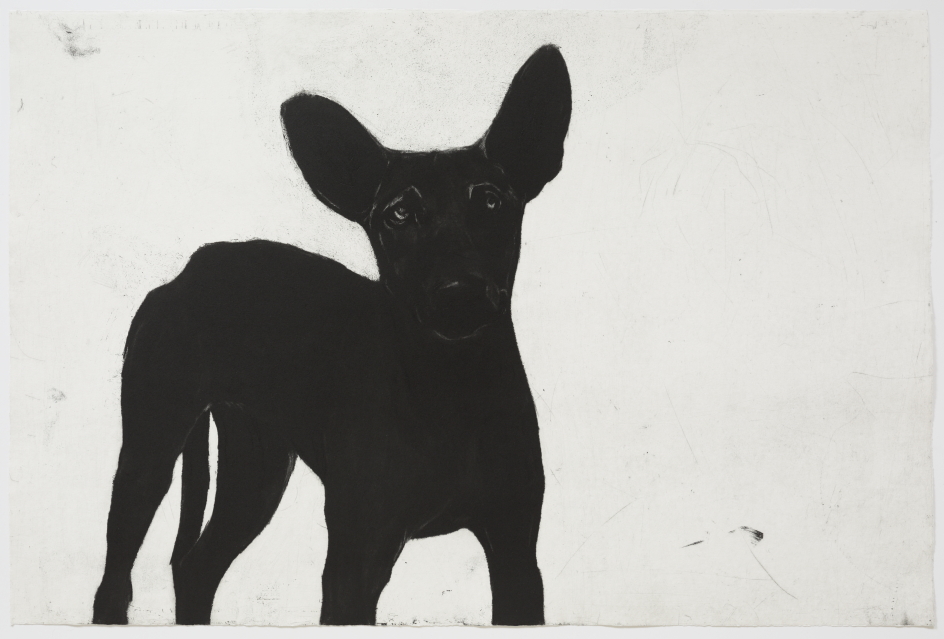

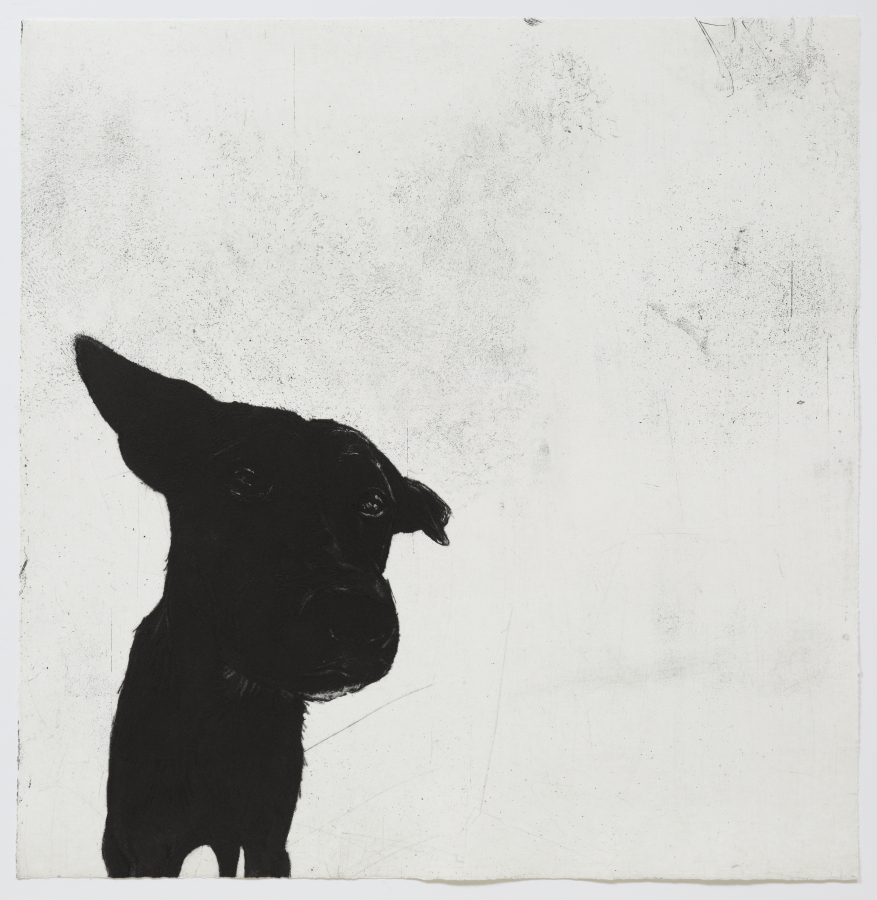

2016 © Deborah Williams, Almost human? Exactly dog 2014, etching, engraving, aquatint and roulette intaglio, 58.5 x 87.5 cm, edition 20

Deborah talks about her recent work:

Images and writings about dogs and puppies often seen as clichéd, kitsch and saccharine in the society we live in. The dismissive attitude to the representation of domestic animals makes it not deserving of scholarly discourse or considered as a subject of serious art making.

The dismissive attitude to the representation of domestic animals may in part be because in the society in which we live, images and writings about dogs and puppies are often seen as clichéd, kitsch and saccharine, not deserving of scholarly discourse or considered as a subject of serious art making.

I seek to avoid the stigma of sentimentality in my images of dogs by relating and depicting the dog outside of the boundaries of the typical pet/owner, dominant/submissive association. Integral to the work and the avoidance of the sentimental is the treatment of the pictorial space within the image. More often than not, the image of the dog inhabits a space devoid of distraction. Where something that has possibly been perceived as ordinary, the dog now becomes emblematic and somewhat sculptural. As the dog is removed from a world of detail so the dog itself can lack detail and display a certain degree of abstraction: we see less, so we imagine more. The non-specific space the dogs inhabit confers ambiguity whilst at the same time, their very presence, whether in silhouette or hint of a dog, is certain. In the works where the dogs are black silhouettes, both the pictorial space is a void and the dog is a void, both present and absent.

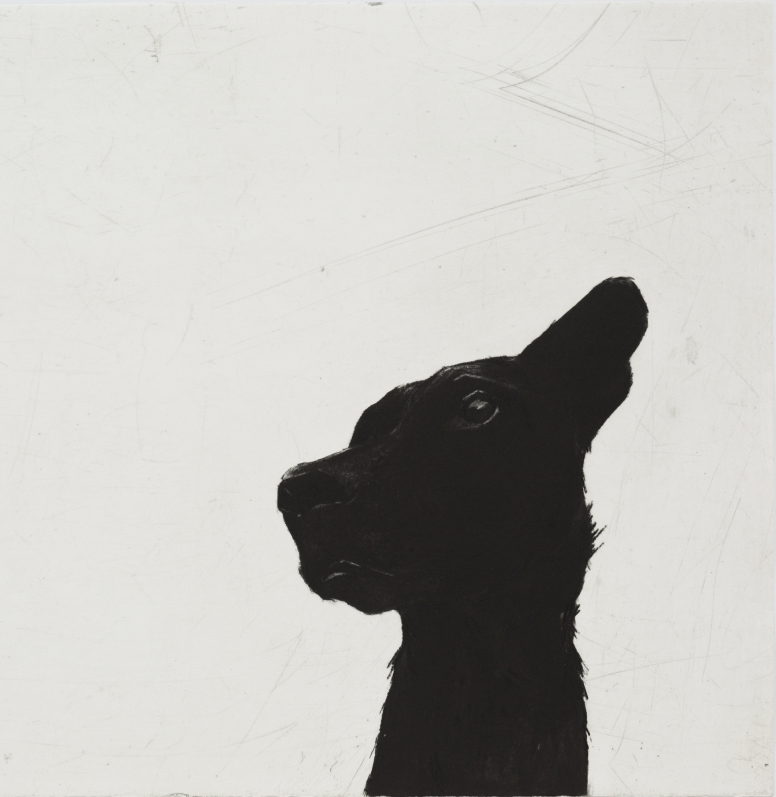

© 2016, Deborah Williams, The seeing other, etching and roulette intaglio, 50.5 x 57.5 cm, edition of 20

The society in which I live generally holds its dogs near and dear. I see dogs that are adored and adorned. We often dress them as people, address them as infants, companion them as life partners, interpreting them solely as part of our human experience, affection, need, and jurisdiction. Their virtues are lauded as service and watchdogs, members of the family and yet we are strangely disconcerted when they disobey our commands, opting instead to display the innate characteristics of their canine selves.

When I look at dogs in and around me, I question whether dogs are seen for what they are, as separate beings. I observe that while we do not objectify our dogs per se our feelings are frequently filtered through human perspectives; these dogs are, therefore, anthropomorphized brought unwittingly into our worlds.

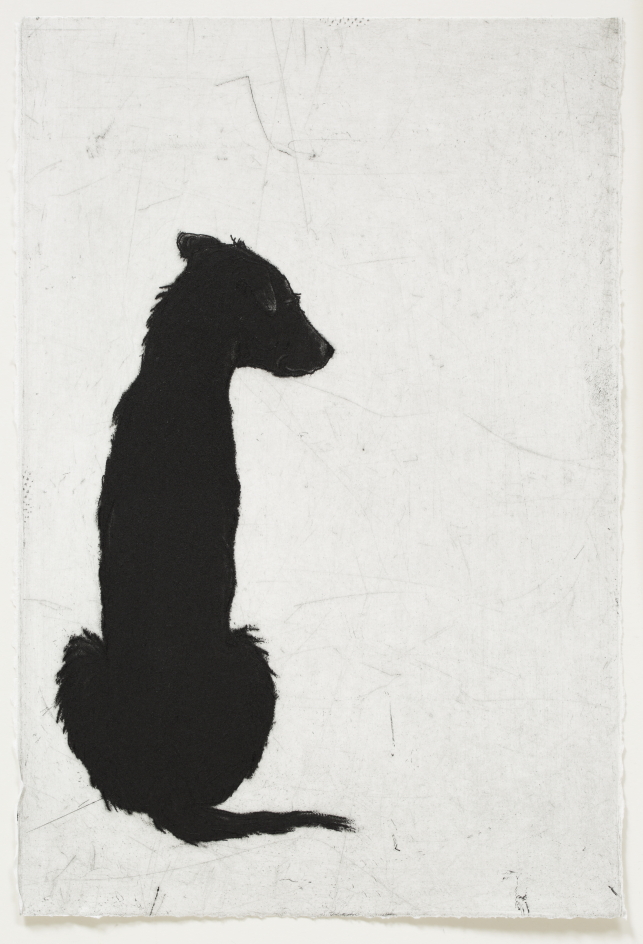

© 2016, Deborah Williams, Held its form, soft ground etching and roulette intaglio, 29.5 x 19.5 cm, edition of 20

I strive to challenge the anthropomorphizing of dogs even though I acknowledge that my work, in common with historical and contemporary contexts of the representation of dogs, is none the less filtered through my own perspectives and brought into our world.

For a dog, it must surely be a complex relationship, enduring and interdependent, loving and loyal, yet simply ‘other’. It is the ‘other’ that I endeavour to depict.

It is this latter context, which I focus on. I aim to depict the dog not as a breed above, apart or beyond, but of its own. Captured in a moment.

I am endeavoring to recognize an animal’s sentience including agency and resistance by avoiding the traditional perspectives of anthropomorphism and domination. Incorporating actions that are initiated by the animal, I aim to acknowledge the animal as subject rather than object, shifting from representation of the animal as a symbol to representing the animal’s presence.

In my work, I now seek to overcome conventional depictions of the animal. I seek to depict the dog as dog and invite the viewer to do the same.

© 2016, Deborah Williams, Survey, etching, engraving, roulette and drypoint intaglio, 56.5 x 55 cm, edition of 20

It’s lunch time and Kenzie needs attention. Later, more administration to solve before I get back into City Shields, The Incessant Journey.